#j. r. moehringer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Personal History

May 15, 2023 Issue

Notes from Prince Harry’s Ghostwriter

Collaborating on his memoir, “Spare,” meant spending hours together on Zoom, meeting his inner circle, and gaining a new perspective on the tabloids.

By J. R. Moehringer

May 8, 2023

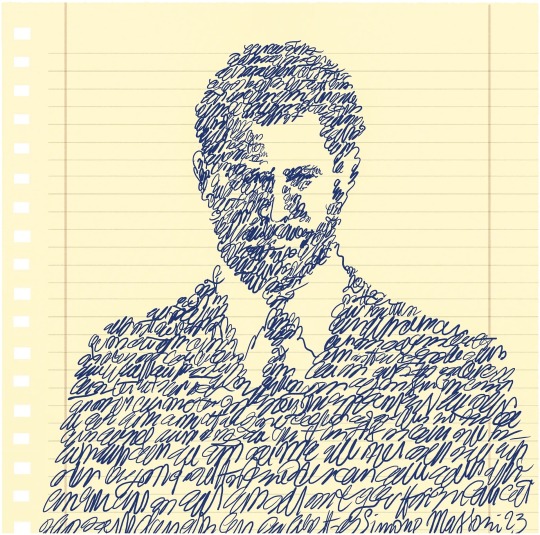

A portrait of Prince Harry composed of scribbles that evoke writing on a yellow piece of binder paper.

Work with Prince Harry on the book proceeded steadily—until the press found out about it.Illustration by Simone Massoni

I was exasperated with Prince Harry. My head was pounding, my jaw was clenched, and I was starting to raise my voice. And yet some part of me was still able to step outside the situation and think, This is so weird. I’m shouting at Prince Harry. Then, as Harry started going back at me, as his cheeks flushed and his eyes narrowed, a more pressing thought occurred: Whoa, it could all end right here.

This was the summer of 2022. For two years, I’d been the ghostwriter on Harry’s memoir, “Spare,” and now, reviewing his latest edits in a middle-of-the-night Zoom session, we’d come to a difficult passage. Harry, at the close of gruelling military exercises in rural England, gets captured by pretend terrorists. It’s a simulation, but the tortures inflicted upon Harry are very real. He’s hooded, dragged to an underground bunker, beaten, frozen, starved, stripped, forced into excruciating stress positions by captors wearing black balaclavas. The idea is to find out if Harry has the toughness to survive an actual capture on the battlefield. (Two of his fellow-soldiers don’t; they crack.) At last, Harry’s captors throw him against a wall, choke him, and scream insults into his face, culminating in a vile dig at—Princess Diana?

Even the fake terrorists engrossed in their parts, even the hard-core British soldiers observing from a remote location, seem to recognize that an inviolate rule has been broken. Clawing that specific wound, the memory of Harry’s dead mother, is out of bounds. When the simulation is over, one of the participants extends an apology.

Harry always wanted to end this scene with a thing he said to his captors, a comeback that struck me as unnecessary, and somewhat inane. Good for Harry that he had the nerve, but ending with what he said would dilute the scene’s meaning: that even at the most bizarre and peripheral moments of his life, his central tragedy intrudes. For months, I’d been crossing out the comeback, and for months Harry had been pleading for it to go back in. Now he wasn’t pleading, he was insisting, and it was 2 a.m., and I was starting to lose it. I said, “Dude, we’ve been over this.”

Why was this one line so important? Why couldn’t he accept my advice? We were leaving out a thousand other things—that’s half the art of memoir, leaving stuff out—so what made this different? Please, I said, trust me. Trust the book.

Although this wasn’t the first time that Harry and I had argued, it felt different; it felt as if we were hurtling toward some kind of decisive rupture, in part because Harry was no longer saying anything. He was just glaring into the camera. Finally, he exhaled and calmly explained that, all his life, people had belittled his intellectual capabilities, and this flash of cleverness proved that, even after being kicked and punched and deprived of sleep and food, he had his wits about him.

“Oh,” I said. “O.K.” It made sense now. But I still refused.

“Why?”

Because, I told him, everything you just said is about you. You want the world to know that you did a good job, that you were smart. But, strange as it may seem, memoir isn’t about you. It’s not even the story of your life. It’s a story carved from your life, a particular series of events chosen because they have the greatest resonance for the widest range of people, and at this point in the story those people don’t need to know anything more than that your captors said a cruel thing about your mom.

Harry looked down. A long time. Was he thinking? Seething? Should I have been more diplomatic? Should I have just given in? I imagined I’d be thrown off the book soon after sunup. I could almost hear the awkward phone call with Harry’s agent, and I was sad. Never mind the financial hit—I was focussed on the emotional shock. All the time, the effort, the intangibles I’d invested in Harry’s memoir, in Harry, would be gone just like that.

After what seemed like an hour, Harry looked up, and we locked eyes. “O.K.,” he said.

“O.K.?”

“Yes. I get it.”

“Thank you, Harry,” I said, relieved.

He shot me a mischievous grin. “I really enjoy getting you worked up like that.”

I burst into laughter and shook my head, and we moved on to his next set of edits.

Later that morning, after a few hours of sleep, I sat outside worrying. (Mornings are my worry time, along with afternoons and evenings.) I didn’t worry so much about the propriety of arguing with princes, or even the risks. One of a ghostwriter’s main jobs is having a big mouth. You win some, you lose most, but you have to keep pushing, not unlike a demanding parent or a tyrannical coach. Otherwise, you’re nothing but a glorified stenographer, and that’s disloyalty to the author, to the book—to books. Opposition is true Friendship, William Blake wrote, and if I had to choose a ghostwriting credo, that would be it.

No, rather than the rightness of going after Harry, I was questioning the heat with which I’d done so. I scolded myself: It’s not your comeback. It’s not your mother. For the thousandth time in my ghostwriting career, I reminded myself: It’s not your effing book.

Some days, the phone doesn’t stop. Ghostwriters in distress. They ask for ten minutes, half an hour. A coffee date.

“My author can’t remember squat.”

“My author and I have come to despise each other.”

“I can’t get my author to call me back—is it normal for a ghost to get ghosted?”

At the outset, I do what ghostwriters do. I listen. And eventually, after the callers talk themselves out, I ask a few gentle questions. The first (aside from “How did you get this number?”) is always: How bad do you want it? Because things can go sideways in a hurry. An author might know nothing about writing, which is why he hired a ghost. But he may also have the literary self-confidence of Saul Bellow, and good luck telling Saul Bellow that he absolutely may not describe an interesting bowel movement he experienced years ago, as I once had to tell an author. So fight like crazy, I say, but always remember that if push comes to shove no one will have your back. Within the text and without, no one wants to hear from the dumb ghostwriter.

I try not to sound didactic. A lot of what I’ve read about ghostwriting, much of it from accomplished ghostwriters, doesn’t square with my experience. Recording the author? Terrible idea—it makes many authors feel as if they’re being deposed. Dressing like the author? It’s a memoir, not a masquerade party. The ghostwriter for Julian Assange wrote twenty-five thousand words about his methodology, and it sounded to me like Elon Musk on mushrooms—on Mars. That same ghost, however, published a review of “Spare” describing Harry as “off his royal tits” and me as going “all Sartre or Faulkner,” so what do I know? Who am I to offer rules? Maybe the alchemy of each ghost-author pairing is unique.

Therefore, I simply remind the callers that ghostwriting is an art and urge them not to let those who cast it as hacky, shady, or faddish (it’s been around for thousands of years) dim their pride. I also tell them that they’re providing a vital public service, helping to shore up the publishing industry, since most of the titles on this week’s best-seller list were written by someone besides the named author.

Signing off, the callers usually sigh and say thanks and grumble something like “Well, whatever happens, I’m never doing this again.” And I tell them yes, they will, and wish them luck.

How does a person even become a ghostwriter? What’s the path into a profession for which there is no school or certification, and to which no one actually aspires? You never hear a kid say, “One day, I want to write other people’s books.” And yet I think I can detect some hints, some foreshadowing in my origins.

When I was growing up in Manhasset, New York, people would ask: Where’s your dad? My typical answer was an embarrassed shrug. Beats me. My old man wasn’t around, that’s all I knew, all any grownup had the heart to tell me. And yet he was also everywhere. My father was a well-known rock-and-roll d.j., so his Sam Elliott basso profundo was like the Long Island Rail Road, rumbling in the distance at maddeningly regular intervals.

Every time I caught his show, I’d feel confused, empty, sad, but also amazed at how much he had to say. The words, the jokes, the patter—it didn’t stop. Was it my Oedipal counterstrike to fantasize an opposite existence, one in which I just STFU? Less talking, more listening, that was my basic life plan at age ten. In Manhasset, an Irish-Italian enclave, I was surrounded by professional listeners: bartenders and priests. Neither of those careers appealed to me, so I waited, and one afternoon found myself sitting with a cousin at the Squire theatre, in Great Neck, watching a matinée of “All the President’s Men.” Reporters seemed to do nothing but listen. Then they got to turn what they heard into stories, which other people read—no talking required. Sign me up.

My first job out of college was at the New York Times. When I wasn’t fetching coffee and corned beef, I was doing “legwork,” which meant running to a fire, a trial, a murder scene, then filing a memo back to the newsroom. The next morning, I’d open the paper and see my facts, maybe my exact words, under someone else’s name. I didn’t mind; I hated my name. I was born John Joseph Moehringer, Jr., and Senior was M.I.A. Not seeing my name, his name, wasn’t a problem. It was a perk.

Many days at the Times, I’d look around the newsroom, with its orange carpet and pipe-puffing lifers and chattering telex machines, and think, I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. And then the editors suggested I go somewhere else.

I went west. I got a job at the Rocky Mountain News, a tabloid founded in 1859. Its first readers were the gold miners panning the rivers and creeks of the Rockies, and though I arrived a hundred and thirty-one years later, the paper still read as if it were written for madmen living alone in them thar hills. The articles were thumb-length, the fact checking iffy, and the newsroom mood, many days, bedlam. Some oldsters were volubly grumpy about being on the back slopes of middling careers, others were blessed with unjustified swagger, and a few were dangerously loose cannons. (I’ll never forget the Sunday morning our religion writer, in his weekly column, referred to St. Joseph as “Christ’s stepdad.” The phones exploded.) The general lack of quality control made the paper a playground for me. I was able to go slow, learn from mistakes without being defined by them, and build up rudimentary skills, like writing fast.

What I did best, I discovered, was write for others. The gossip columnist spent most nights in downtown saloons, hunting for scoops, and some mornings he’d shuffle into the newsroom looking rough. One morning, he fixed his red eyes on me, gestured toward his notes, and rasped, “Would you?” I sat at his desk and dashed off his column in twenty minutes. What a rush. Writing under no name was safe; writing under someone else’s name (and picture) was hedonic—a kind of hiding and seeking. Words had never come easy for me, but, when I wrote as someone else, the words, the jokes, the patter—it didn’t stop.

In the fall of 2006, my phone rang. Unknown number. But I instantly recognized the famously soft voice: for two decades, he’d loomed over the tennis world. Now, on the verge of retiring, he told me that he was decompressing from the emotions of the moment by reading my memoir, “The Tender Bar,” which had recently been published. It had him thinking about writing his own. He wondered if I’d come talk to him about it. A few weeks later, we met at a restaurant in his home town, Las Vegas.

Andre Agassi and I were very different, but our connection was instant. He had an eighth-grade education but a profound respect for people who read and write books. I had a regrettably short sporting résumé (my Little League fastball was unhittable) but deep reverence for athletes. Especially the solitaries: tennis players, prizefighters, matadors, who possess that luminous charisma which comes from besting opponents single-handedly. But Andre didn’t want to talk about that. He hated tennis, he said. He wanted to talk about memoir. He had a list of questions. He asked why my memoir was so confessional. I told him that’s how you know you can trust an author—if he’s willing to get raw.

He asked why I’d organized my memoir around other people, rather than myself. I told him that was the kind of memoir I admired. There’s so much power to be gained, and honesty to be achieved, from taking an ostensibly navel-gazing genre and turning the gaze outward. Frank McCourt had a lot of feelings about his brutal Irish childhood, but he kept most of them to himself, focussing instead on his Dad, his Mam, his beloved siblings, the neighbors down the lane.

“I am a part of all that I have met.” It might’ve been that first night, or another, but at some point I shared that line from Tennyson, and Andre loved it. The same almost painful gratitude that I felt toward my mother, and toward my bartender uncle and his barfly friends, who helped her raise me, Andre felt for his trainer and his coach, and for his wife, Stefanie Graf.

But how, he asked, do you write about other people without invading their privacy? That’s the ultimate challenge, I said. I sought permission from nearly everyone I wrote about, and shared early drafts, but sometimes people aren’t speaking to you, and sometimes they’re dead. Sometimes, in order to tell the truth, you simply can’t avoid hurting someone’s feelings. It goes down easier, I said, if you’re equally unsparing about yourself.

He asked if I’d help him do it. I gave him a soft no. I liked his enthusiasm, his boldness—him. But I’d never imagined myself writing someone else’s book, and I already had a job. By now, I’d left the Rocky Mountain News and joined the Los Angeles Times. I was a national correspondent, doing long-form journalism, which I loved. Alas, the Times was about to change. A new gang of editors had come in, and not long after my dinner with Andre they let it be known that the paper would no longer prioritize long-form journalism.

Apart from a beef with my bosses, and apart from the money (Andre was offering a sizable bump from my reporter salary), what finally made me change my no to a yes, put my stuff into storage, and move to Vegas was the sense that Andre was suffering an intense and specific ache that I might be able to cure. He wanted to tell his story and didn’t know how; I’d been there. I’d struggled for years to tell my story.

Every attempt failed, and every failure took a heavy psychic toll. Some days, it felt like a physical blockage, and to this day I believe my story would’ve remained stuck inside me forever if not for one editor at the Times, who on a Sunday afternoon imparted some thunderbolt advice about memoir that steered me onto the right path. I wanted to give Andre that same grace.

Shortly before I moved to Vegas, a friend invited me to a fancy restaurant in the Phoenix suburbs for a gathering of sportswriters covering the 2008 Super Bowl. As the menus were being handed around, my friend clinked a knife against his glass and announced, “O.K., listen up! Moehringer here has been asked by Agassi to ghostwrite his—”

Groans.

“Exactly. We’ve all done our share of these fucking things—”

Louder groans.

“Right! Our mission is not to leave this table until we’ve convinced this idiot to tell Agassi not just no but hell no.”

At once, the meal turned into a raucous meeting of Ghostwriters Anonymous. Everyone had a hard-luck story about being disrespected, dismissed, shouted at, shoved aside, abused in a hilarious variety of ways by an astonishing array of celebrities, though I mostly remember the jocks. The legendary basketball player who wouldn’t come to the door for his first appointment with his ghost, then appeared for the second buck naked. The hockey great with the personality of a hockey stick, who had so few thoughts about his time on this planet, so little interest in his own book, that he gave his ghost an epic case of writer’s block. The notorious linebacker who, days before his memoir was due to the publisher, informed his ghost that the co-writing credit would go to his psychotherapist.

Between gasping and laughing, I asked the table, “Why do they do it? Why do they treat ghostwriters so badly?” I was bombarded with theories.

Authors feel ashamed about needing someone to write their story, and that shame makes them behave in shameful ways.

Authors think they could write the book themselves, if only they had time, so they resent having to pay you to do it.

Authors spend their lives safeguarding their secrets, and now you come along with your little notebook and pesky questions and suddenly they have to rip back the curtain? Boo.

But if all authors treat all ghosts badly, I wondered, and if it’s not your book in the first place, why not cash the check and move on? Why does it hurt so much? I don’t recall anyone having a good answer for that.

“Please,” I said to Andre, “don’t give me a story to tell at future Super Bowls.” He grinned and said he’d do his best. He did better than that. In two years of working together, we never exchanged a harsh word, not even when he felt my first draft needed work.

Maybe the Germans have a term for it, the particular facial expression of someone reading something about his life that’s even the tiniest bit wrong. Schaudergesicht? I saw that look on Andre’s face, and it made me want to lie down on the floor. But, unlike me, he didn’t overreact. He knew that putting a first serve into the net is no big deal. He made countless fixes, and I made fixes to his fixes, and together we made ten thousand more, and in time we arrived at a draft that satisfied us both. The collaboration was so close, so synchronous, you’d have to call the eventual voice of the memoir a hybrid—though it’s all Andre. That’s the mystic paradox of ghostwriting: you’re inherent and nowhere; vital and invisible. To borrow an image from William Gass, you’re the air in someone else’s trumpet.

“Open,” by Andre Agassi, was published on November 9, 2009. Andre was pleased, reviewers were complimentary, and I soon had offers to ghost other people’s memoirs. Before deciding what to do next, I needed to get away, clear my head. I went to the Green Mountains. For two days, I drove around, stopped at wayside meadows, sat under trees and watched the clouds—until one late afternoon I began feeling unwell. I bought some cold medicine, pulled into the first bed-and-breakfast I saw, and climbed into bed. Hand-sewn quilt under my chin, I switched on the TV. There was Andre, on a late-night talk show.

The host was praising “Open,” and Agassi was being his typical charming, humble self. Now the host was praising the writing. Agassi continued to be humble. Thank you, thank you. But I dared to hope he might mention . . . me? An indefensible, illogical hope: Andre had asked me to put my name on the cover, and I’d declined. Nevertheless, right before zonking out, I started muttering at the TV, “Say my name.” I got a bit louder. “Say my name!” I got pretty rowdy. “Say my fucking name!”

Seven hours later, I stumbled downstairs to the breakfast room and caught a weird vibe. Guests stared. Several peered over my shoulder to see who was with me. What the? I sat alone, eating some pancakes, until I got it. The bed-and-breakfast had to be three hundred years old, with walls made of pre-Revolutionary cardboard—clearly every guest had heard me. Say my name!

I took it as a lesson. NyQuil was to blame, but also creeping narcissism. The gods were admonishing me: You can’t be Mister Rogers while ghosting the book and John McEnroe when it’s done. I drove away from Vermont with newfound clarity. I’m not cut out for this ghostwriting thing. I needed to get back to my first love, journalism, and to writing my own books.

During the next year or so, I freelanced for magazines while making notes for a novel. Then once more to the wilderness. I rented a tiny cabin in the far corner of nowhere and, for a full winter, rarely left. No TV, no radio, no Wi-Fi. For entertainment, I listened to the silver foxes screaming at night in a nearby forest, and I read dozens of books. But mostly I sat before the woodstove and tried to inhabit the minds of my characters. The novel was historical fiction, based on the decades-long crime spree of America’s most prolific bank robber, but also based on my disgust with the bankers who had recently devastated the global financial system. In real life, my bank-robbing protagonist wrote a memoir, with a ghostwriter, which was full of lies or delusions. I thought it might be fascinating to override that memoir with solid research, overwrite the ghostwriter, and become, in effect, the ghostwriter of the ghostwriter of a ghost.

I gave everything I had to that novel, but when it was published, in 2012, it got mauled by an influential critic. The review was then instantly tweeted by countless humanitarians, often with sidesplitting commentary like “Ouch.” I was on book tour at the time and read the review in a pitch-dark hotel room knowing full well what it meant: the book was stillborn. I couldn’t breathe, couldn’t stand. Part of me wanted to never leave that room. Part of me never did.

I barely slept or ate for months. My savings ran down. Occasionally, I’d take on a freelance assignment, profile an athlete for a magazine, but mostly I was in hibernation. Then one day the phone rang. A soft voice, vaguely familiar. Andre, asking if I was up for working with someone on a memoir.

Who?

Phil Knight.

Who?

Andre sighed. Founder of Nike?

A business book didn’t seem like my thing. But I needed to do something, and writing my own stuff was out. I went to the initial meeting thinking, It’s only an hour of my life. It wound up being three years.

Luckily, Phil had no interest in doing the typical C.E.O. auto-hagiography. He’d sought writing advice from Tobias Wolff, he was pals with a Pulitzer-winning novelist. He wanted to write a literary memoir, unfolding his mistakes, his anxieties—his quest. He viewed entrepreneurship, and sports, as a spiritual search. (He’d read deeply in Taoism and Zen.) Since I, too, was in search of meaning, I thought his book might be just the thing I needed.

It was. It was also, in every sense of that overused phrase, a labor of love. (I married the book’s editor.) When “Shoe Dog” was published, in April, 2016, I reflected on the dire warnings I’d heard at Super Bowl XLII and thought, What were they talking about? I felt like a guy, warned off by a bunch of wizened gamblers, who hits the jackpot twice with the first two nickels he sticks into a slot machine. Then again, I figured, better quit while I’m ahead.

Back to magazine writing. I also dared to start another novel. More personal, more difficult than the last, it absorbed me totally and I was tunnelling toward a draft while also starting a family. There was no time for anything else, no desire. And yet some days I’d hear that siren call. An actor, an activist, a billionaire, a soldier, a politician, another billionaire, a lunatic would phone, seeking help with a memoir.

Twice I said yes. Not for the money. I’ve never taken a ghosting gig for the money. But twice I felt that I had no choice, that the story was too cool, the author just too compelling, and twice the author freaked out at my first draft. Twice I explained that first drafts are always flawed, that error is the mother of truth, but it wasn’t just the errors. It was the confessions, the revelations, the cold-blooded honesty that memoir requires. Everyone says they want to get raw until they see how raw feels.

Twice the author killed the book. Twice I sat before a stack of pages into which I’d poured my soul and years of my life, knowing they were good, and knowing that they were about to go into a drawer forever. Twice I said to my wife, Never again.

And then, in the summer of 2020, I got a text. The familiar query. Would you be interested in speaking with someone about ghosting a memoir? I shook my head no. I covered my eyes. I picked up the phone and heard myself blurting, Who?

Prince Harry.

I agreed to a Zoom. I was curious, of course. Who wouldn’t be? I wondered what the real story was. I wondered if we’d have any chemistry. We did, and there was, I think, a surprising reason. Princess Diana had died twenty-three years before our first conversation, and my mother, Dorothy Moehringer, had just died, and our griefs felt equally fresh.

Still, I hesitated. Harry wasn’t sure how much he wanted to say in his memoir, and that concerned me. I’d heard similar reservations, early on, from both authors who’d ultimately killed their memoirs. Also, I knew that whatever Harry said, whenever he said it, would set off a storm. I am not, by nature, a storm chaser. And there were logistical considerations. In the early stages of a global pandemic, it was impossible to predict when I’d be able to sit down with Harry in the same room. How do you write about someone you can’t meet?

Harry had no deadline, however, and that enticed me. Many authors are in a hot hurry, and some ghosts are happy to oblige. They churn and burn, producing three or four books a year. I go painfully slow; I don’t know any other way. Also, I just liked the dude. I called him dude right away; it made him chuckle. I found his story, as he outlined it in broad strokes, relatable and infuriating. The way he’d been treated, by both strangers and intimates, was grotesque. In retrospect, though, I think I selfishly welcomed the idea of being able to speak with someone, an expert, about that never-ending feeling of wishing you could call your mom.

Harry and I made steady progress in the course of 2020, largely because the world didn’t know what we were up to. We could revel in the privacy of our Zoom bubble. As Harry grew to trust me, he brought other people into the bubble, connecting me with his inner circle, a vital phase in every ghosting job. There is always someone who knows your author’s life better than he does, and your task is to find that person fast and interview his socks off.

As the pandemic waned, I was finally able to travel to Montecito. I went once with my wife and children. (Harry won the heart of my daughter, Gracie, with his vast “Moana” scholarship; his favorite scene, he told her, is when Heihei, the silly chicken, finds himself lost at sea.) I also went twice by myself. Harry put me up in his guesthouse, where Meghan and Archie would visit me on their afternoon walks. Meghan, knowing I was missing my family, was forever bringing trays of food and sweets.

Little by little, Harry and I amassed hundreds of thousands of words. When we weren’t Zooming or phoning, we were texting around the clock. In due time, no subject was off the table. I felt honored by his candor, and I could tell that he felt astonished by it. And energized. While I always emphasized storytelling and scenes, Harry couldn’t escape the wish that “Spare” might be a rebuttal to every lie ever published about him. As Borges dreamed of endless libraries, Harry dreams of endless retractions, which meant no end of revelations. He knew, of course, that some people would be aghast at first. “Why on earth would Harry talk about that?” But he had faith that they would soon see: because someone else already talked about it, and got it wrong.

He was joyful at this prospect; everything in our bubble was good. Then someone leaked news of the book.

Whoever it was, their callousness toward Harry extended to me. I had a clause in my contract giving me the right to remain unidentified, a clause I always insist on, but the leaker blew that up by divulging my name to the press. Along with pretty much anyone who has had anything to do with Harry, I woke one morning to find myself squinting into a gigantic searchlight. Every hour, another piece would drop, each one wrong. My fee was wrong, my bio was wrong, even my name.

One royal expert cautioned that, because of my involvement in the book, Harry’s father should be “looking for a pile of coats to hide under.” When I mentioned this to Harry, he stared. “Why?”

“Because I have daddy issues.” We laughed and got back to discussing our mothers.

The genesis of my relationship with Harry was constantly misreported. Harry and I were introduced by George Clooney, the British newspapers proclaimed, even though I’ve never met George Clooney. Yes, he was directing a film based on my memoir, but I’ve never been in the man’s presence, never communicated with him in any way. I wanted to correct the record, write an op-ed or something, tweet some facts. But no. I reminded myself: ghosts don’t speak. One day, though, I did share my frustration with Harry. I bemoaned that these fictions about me were spreading and hardening into orthodoxy. He tilted his head: Welcome to my world, dude. By now, Harry was calling me dude.

A week before its pub date, “Spare” was leaked. A Madrid bookshop reportedly put embargoed copies of the Spanish version on its shelves, “by accident,” and reporters descended. In no time, Fleet Street had assembled crews of translators to reverse-engineer the book from Spanish to English, and with so many translators working on tight deadline the results read like bad Borat. One example among many was the passage about Harry losing his virginity. Per the British press, Harry recounts, “I mounted her quickly . . .” But of course he doesn’t. I can assert with one-hundred-per-cent confidence that no one gets “mounted,” quickly or otherwise, in “Spare.”

I didn’t have time to be horrified. When the book was officially released, the bad translations didn’t stop. They multiplied. The British press now converted the book into their native tongue, that jabberwocky of bonkers hot takes and classist snark. Facts were wrenched out of context, complex emotions were reduced to cartoonish idiocy, innocent passages were hyped into outrages—and there were so many falsehoods. One British newspaper chased down Harry’s flight instructor. Headline: “Prince Harry’s army instructor says story in Spare book is ‘complete fantasy.’ ” Hours later, the instructor posted a lengthy comment beneath the article, swearing that those words, “complete fantasy,” never came out of his mouth. Indeed, they were nowhere in the piece, only in the bogus headline, which had gone viral. The newspaper had made it up, the instructor said, stressing that Harry was one of his finest students.

The only other time I’d witnessed this sort of frenzied mob was with LeBron James, whom I’d interviewed before and after his decision to leave the Cleveland Cavaliers and join the Miami Heat. I couldn’t fathom the toxic cloud of hatred that trailed him. Fans, particularly Cavs loyalists, didn’t just decry James. They wished him dead. They burned his jersey, threw rocks at his image. And the media egged them on. In those first days of “Spare,” I found myself wondering what the ecstatic contempt for Prince Harry and King James had in common. Racism, surely. Also, each man had committed the sin of publicly spurning his homeland. But the biggest factor, I came to believe, was money. In times of great economic distress, many people are triggered by someone who has so much doing anything to try to improve his lot.

Within days, the amorphous campaign against “Spare” seemed to narrow to a single point of attack: that Harry’s memoir, rigorously fact-checked, was rife with errors. I can’t think of anything that rankles quite like being called sloppy by people who routinely trample facts in pursuit of their royal prey, and this now happened every few minutes to Harry and, by extension, to me. In one section of the book, for instance, Harry reveals that he used to live for the yearly sales at TK Maxx, the discount clothing chain. Not so fast, said the monarchists at TK Maxx corporate, who rushed out a statement declaring that TK Maxx never has sales, just great savings all the time! Oh, snap! Gotcha, Prince George Santos! Except that people around the world immediately posted screenshots of TK Maxx touting sales on its official Twitter account. (Surely TK Maxx’s effort to discredit Harry’s memoir was unrelated to the company’s long-standing partnership with Prince Charles and his charitable trust.)

Ghostwriters don’t speak, I reminded myself over and over. But I had to do something. So I ventured one small gesture. I retweeted a few quotes from Mary Karr about inadvertent error in memories and memoir, plus seemingly innocuous quotes from “Spare” about the way Harry’s memory works. (He can’t recall much from the years right after his mother died, and for the most part remembers places better than people—possibly because places didn’t let him down the way people did.) Smooth move, ghostwriter. My tweets were seized upon, deliberately misinterpreted by trolls, and turned into headlines by real news outlets. Harry’s ghostwriter admits the book is all lies.

One of Harry’s friends gave a book party. My wife and I attended.

We were feeling fragile as we arrived, and it had nothing to do with Twitter. Days earlier, we’d been stalked, followed in our car as we drove our son to preschool. When I lifted him out of his seat, a paparazzo leaped from his car and stood in the middle of the road, taking aim with his enormous lens and scaring the hell out of everyone at dropoff. Then, not one hour later, as I sat at my desk, trying to calm myself, I looked up to see a woman’s face at my window. As if in a dream, I walked to the window and asked, “Who are you?” Through the glass, she whispered, “I’m from the Mail on Sunday.”

I lowered the shade, phoned an old friend—the same friend whose columns I used to ghostwrite in Colorado. He listened but didn’t get it. How could he get it? So I called the only friend who might.

It was like telling Taylor Swift about a bad breakup. It was like singing “Hallelujah” to Leonard Cohen. Harry was all heart. He asked if my family was O.K., asked for physical descriptions of the people harassing us, promised to make some calls, see if anything could be done. We both knew nothing could be done, but still. I felt gratitude, and some regret. I’d worked hard to understand the ordeals of Harry Windsor, and now I saw that I understood nothing. Empathy is thin gruel compared with the marrow of experience. One morning of what Harry had endured since birth made me desperate to take another crack at the pages in “Spare” that talk about the media.

Too late. The book was out, the party in full swing. As we walked into the house, I looked around, nervous, unsure of what state we’d find the author in. Was he, too, feeling fragile? Was he as keen as I was to organize a global boycott of TK Maxx?

He appeared, marching toward us, looking flushed. Uh-oh, I thought, before registering that it was a good flush. His smile was wide as he embraced us both. He was overjoyed by many things. The numbers, naturally. Guinness World Records had just certified his memoir as the fastest-selling nonfiction book in the history of the world. But, more than that, readers were reading, at last, the actual book, not Murdoched chunks laced with poison, and their online reviews were overwhelmingly effusive. Many said Harry’s candor about family dysfunction, about losing a parent, had given them solace.

The guests were summoned into the living room. There were several lovely toasts to Harry, then the Prince stepped forward. I’d never seen him so self-possessed and expansive. He thanked his publishing team, his editor, me. He mentioned my advice, to “trust the book,” and said he was glad that he did, because it felt incredible to have the truth out there, to feel—his voice caught—“free.” There were tears in his eyes. Mine, too.

And yet once a ghost, always a ghost. I couldn’t help obsessing about that word “free.” If he’d used that in one of our Zoom sessions, I’d have pushed back. Harry first felt liberated when he fell in love with Meghan, and again when they fled Britain, and what he felt now, for the first time in his life, was heard. That imperious Windsor motto, “Never complain, never explain,” is really just a prettified omertà, which my wife suggests might have prolonged Harry’s grief. His family actively discourages talking, a stoicism for which they’re widely lauded, but if you don’t speak your emotions you serve them, and if you don’t tell your story you lose it—or, what might be worse, you get lost inside it. Telling is how we cement details, preserve continuity, stay sane. We say ourselves into being every day, or else. Heard, Harry, heard—I could hear myself making the case to him late at night, and I could see Harry’s nose wrinkle as he argued for his word, and I reproached myself once more: Not your effing book.

But, after we hugged Harry goodbye, after we thanked Meghan for toys she’d sent our children, I had a second thought about silence. Ghosts don’t speak—says who? Maybe they can. Maybe sometimes they should.

Several weeks later, I was having breakfast with my family. The children were eating and my wife and I were talking about ghostwriting. Someone had just called, seeking help with their memoir. Intriguing person, but the answer was going to be no. I wanted to resume work on my novel. Our five-year-old daughter looked up from her cinnamon toast and asked, “What is ghostwriting?”

My wife and I gazed at each other as if she’d asked, What is God?

“Well,” I said, drawing a blank. “O.K., you know how you love art?”

She nodded. She loves few things more. An artist is what she hopes to be.

“Imagine if one of your classmates wanted to say something, express something, but they couldn’t draw. Imagine if they asked you to draw a picture for them.”

“I would do it,” she said.

“That’s ghostwriting.”

It occurred to me that this might be the closest I’d ever come to a workable definition. It certainly landed with our daughter. You could see it in her eyes. She got off her chair and leaned against me. “Daddy, I will be your ghostwriter.”

My wife laughed. I laughed. “Thank you, sweetheart,” I said.

But that wasn’t what I wanted to say. What I wanted to say was “No, Gracie. Nope. Keep doing your own pictures.” ♦

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am in no way a royalist, but with TV shows like The Crown and never-ending news coverage of royal drama, it was a bit hard to avoid hearing about this book. It generated a bit of a media storm when it came out, with plenty of eyebrow-raising quotes being eagerly shared by news outlets – especially those related to Prince Harry’s sex life. Ultimately, it was curiosity that let me to spending a…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Note

it’s looks like the ghost writer of spare has spoke out

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12060033/amp/I-exasperated-Prince-Harrys-Spare-ghostwriter-J-R-Moehringer-tells-tensions-them.html

Uh oh.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finally got Spare by Prince Harry (and ghostwriter J. R. Moehringer) from the library. I’m not far, but one thing I can say is that the writing is excellent. It’s a pleasure to read. It’s making me want to look up other memoirs that Moehringer has ghostwritten.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just know that Taylor was charmed when Travis told J. R. Moehringer that she does it in eras in his WSJ interview last year.

0 notes

Photo

The greatest players use anger as fuel. Michael Jordan played every night with something like road rage. J. R. Moehringer

0 notes

Text

Spare

by Prince Harry

A month ago, I grabbed Harry's Spare from the online library and finished it in time for it to become Amazon's top-selling book in 2023. Huzza!

The exceptional writing of J. R. Moehringer and Harry's own account make this memoir akin to binge-watching a Netflix series.

Royalists perceive this autobiography as Harry's opportunity to express his discontent and demonstrate his disloyalty towards the royal family. I believe that he is attempting to overcome his emotional and mental scars that have plagued him since his youth. After losing his mother at the tender age of twelve, every important event in his life has been a battle for privacy.

Harry has consistently expressed his disapproval towards the paparazzi. Those he loved have also been affected by the relentless tabloid attacks and stalking. When his attempts to address the media harassment with the Royal Household were met with disdain, he decided to sue a prominent British newspaper for phone hacking, which his father considered to be a suicide mission.

The absence of William's assistance revealed Harry's tangled ties to his elder brother. The heir to the British throne frequently utilized his power dynamics to win arguments and declined any chance to collaborate. When issues concerning their spouses and staff were raised, they reached a point of heated contention. Their constant disagreements have led to Meghan being treated as an outsider by the Royal Household.

At the Sandringham Summit, Harry was blind sided by the schemes of "The Bee, The Fly, and The Wasp", which further strained his relationship with Charles and William. He had to abandon his duties as a royal in exchange for a break from the royal family, even though he wanted to keep working.

Harry shared some good memories from his school and military experiences. Teej and Mike, his mentors, helped him find peace and tranquillity in Botswana when things got too hectic at home. They also urged him to continue his efforts to preserve the wildlife in South Africa.

The memories of his mother and the people who taught him empathy motivated his desire to always help others. These attributes serve as a catalyst for him to embark on a journey of faith to attain his liberation.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Er erzählte mir von seinem Leben, oder dem Leben, von dem er wollte, dass ich dachte, er hätte es geführt, voller Abenteuer und Gefahr und Glanz. Er ließ seine Vergangenheit romantisch klingen, um uns beide von seiner Gegenwart abzulenken, die ziemlich düster aussah. Er hatte sein Talent vergeudet, sein Geld durchgebracht und stand am Beginn eines langen Abstiegs. Er erzählte eine Geschichte nach der anderen ... und ich sagte nichts. Ich hörte genau zu und glaubte jedes Wort, jede Lüge, auch wenn ich sie als solche enttarnte, aber ich war ebenso überzeugt, dass er es bemerkte und mir nur so viele Geschichten erzählte, weil er meine ungeteilte Aufmerksamkeit und Leichtgläubigkeit zu schätzen wusste.

(J. R. Moehringer: Tender Bar)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

J. R. Moehringer on the beauty of telling stories, from The New Yorker, 2023.

#quotes#dark academia#philosophy#poetic#poetry#books and libraries#dark#literature aesthetics#choices#dark acadamia aesthetic#stoicism#omerta#omertà#never complain never explain

0 notes

Text

Prince Harry: Butt hurt over everything!

0 notes

Text

Er benutzte ein unglaubliches Gemisch aus hochgestochenen Wörtern und Gangsterslang, … Er redete gewählt wie William F. Buckley und vulgär wie Häftlinge in Zellenblock C. … Er hielt eine nicht angezündete Zigarette extrem lange in der Hand, … Dann riss er mit großspuriger Geste ein Streichholz an und hielt die Flamme an die Zigarettenspitze. Der nächste abgerundete Satz aus seinem Mund wurde von einer Rauchwolke umhüllt. …

(J. R. Moehringer: Tender Bar)

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12060033/I-exasperated-Prince-Harrys-Spare-ghostwriter-J-R-Moehringer-tells-tensions-them.html

1 note

·

View note

Link

By James Fox

January 18, 2023

There’s some analogy to be had between a ghostwriter and a tailor—both have got to make their client look well cut and elegant, and maybe conceal the flaws or the flab.

I once had some suits made by a retired Savile Row tailor called Harry Cooper for a good price. He was a gifted cutter of cloth, but on one final fitting something didn’t seem to sit well. “It’s nothing to do with the suit,” said Harry, curtly. “It’s the inner man.” No answer to that. What can you do about the inner man? Well, there are tricks, which Harry knew, and he fixed me. A tailor, maybe a butler, too.

A friend was ghostwriting for a famous musician, while I was doing the same, in my case for Keith Richards. “How do you get on with your gentleman?” my friend asked. “My gentleman is being very difficult,” he said. “He won’t let me talk to any of his friends.”

That would have gone against my first trick for ghostwriting: unless a subject is already an accomplished, self-examining writer, novelist, or diarist, no one can successfully, or entertainingly, review their lives by themselves. They will leave half of the good bits out. Somewhere in Life, by Keith Richards, he asserts that “memory is fiction”—a version of the royal riposte “Recollections may vary.” Sam Shepard, the actor and playwright, waved his copy of Life at an audience, recommending, admiringly, this nugget of truth from the pen of Keef.

Friends will trigger memories lost in the lacunae of time, which the writer can retell. Friends keep the story honest; they add wit and the all-important tone of self-effacing humility in the stories the writer can allow to be retold. My friend was writing with one arm tied behind his back, and it showed, to his chagrin, in the final product.

Spare, Prince Harry’s memoir, didn’t have any of this, evidently. Beyond the fury and desire for atonement, no quest for the inner man was on the cards, as was the case in his ghostwriter J. R. Moehringer’s much-praised book with Andre Agassi.

Moehringer didn’t have at his disposal tales of achievement, fascinating friends, mentors, discoveries, creative breakthroughs. He is reported to have done a good job with what he had—a mass of new details on stories already known, some tabloid fodder we didn’t know (cocaine, the roll in the hay), and the descending arc into denunciation and piety. His main task was to write with pace.

Nor was it his task to improve Harry’s prose, in case it spoiled the authenticity. Philip Hensher wondered whether it was Harry’s or Moehringer’s description of the elephants at the Okavango swamp and who was responsible for the phrase “Her tears glistened in the spring sunshine.” He wasn’t enthralled either way.

Without wit, such a book will be charmless and unsympathetic.

In the two published autobiographies I have worked on, some of the funniest and most revealing moments came from the outside.

For surrealism there was the story the producer Don Smith told me about Richards’s forceful mother, Doris, coming to New York when Richards was rehearsing with his band the X-Pensive Winos, a moment when Jack Daniel’s and other stuff was flowing hard and beginning to impair their performance.

It was an incident Richards had forgotten. Doris was watching through the studio glass. The band had been talking for 20 minutes. Smith had shown Doris the talkback button, and she hit it and screamed at Richards, the great Waddy Wachtel, and the great Steve Jordan, “You boys stop messing around there and get to work. This studio is costing money. Nobody understands what you’re saying anyway. I’ve flown all the way from bloody England. I don’t have all night to sit around listening to you yapping about nothing, so get to bloody work.”

“So thanks to Doris’s sudden burst of wrath,” wrote Richards, “we renewed our labours.”

Then there is the story of David Bailey, whose memoir, Look Again, I ghostwrote. When I sensed that Bailey wasn’t being entirely honest, or perhaps was over-romanticizing his relationships with some of the women in his life, I put them together and recorded the dialogue, then printed some of it in the book. First Jean Shrimpton, and then Penelope Tree, his model and girlfriend in the 1960s. At lunch with the three of us, there was a major disagreement about the when and where of the first kiss, as in:

Bailey: That was the first time we did it.

Tree: I swear to God it was not.

And then their breakup:

Tree: I packed two suitcases containing clothes and books and left.

Bailey: I couldn’t find you. You went to Barbados. Then you went off somewhere in the Far East.

Tree: No, first I went to live in a valet’s room on the top story of the Ritz. Which sounds fun, but it wasn’t.

Bailey: I tried to get you back.

Tree: How come I didn’t know about it then?

Keith is right. Memory is fiction.

Or was it me who said it? I can’t remember.

0 notes

Link

By James Fox

January 18, 2023

There’s some analogy to be had between a ghostwriter and a tailor—both have got to make their client look well cut and elegant, and maybe conceal the flaws or the flab.

I once had some suits made by a retired Savile Row tailor called Harry Cooper for a good price. He was a gifted cutter of cloth, but on one final fitting something didn’t seem to sit well. “It’s nothing to do with the suit,” said Harry, curtly. “It’s the inner man.” No answer to that. What can you do about the inner man? Well, there are tricks, which Harry knew, and he fixed me. A tailor, maybe a butler, too.

A friend was ghostwriting for a famous musician, while I was doing the same, in my case for Keith Richards. “How do you get on with your gentleman?” my friend asked. “My gentleman is being very difficult,” he said. “He won’t let me talk to any of his friends.”

That would have gone against my first trick for ghostwriting: unless a subject is already an accomplished, self-examining writer, novelist, or diarist, no one can successfully, or entertainingly, review their lives by themselves. They will leave half of the good bits out. Somewhere in Life, by Keith Richards, he asserts that “memory is fiction”—a version of the royal riposte “Recollections may vary.” Sam Shepard, the actor and playwright, waved his copy of Life at an audience, recommending, admiringly, this nugget of truth from the pen of Keef.

Friends will trigger memories lost in the lacunae of time, which the writer can retell. Friends keep the story honest; they add wit and the all-important tone of self-effacing humility in the stories the writer can allow to be retold. My friend was writing with one arm tied behind his back, and it showed, to his chagrin, in the final product.

Spare, Prince Harry’s memoir, didn’t have any of this, evidently. Beyond the fury and desire for atonement, no quest for the inner man was on the cards, as was the case in his ghostwriter J. R. Moehringer’s much-praised book with Andre Agassi.

Moehringer didn’t have at his disposal tales of achievement, fascinating friends, mentors, discoveries, creative breakthroughs. He is reported to have done a good job with what he had—a mass of new details on stories already known, some tabloid fodder we didn’t know (cocaine, the roll in the hay), and the descending arc into denunciation and piety. His main task was to write with pace.

Nor was it his task to improve Harry’s prose, in case it spoiled the authenticity. Philip Hensher wondered whether it was Harry’s or Moehringer’s description of the elephants at the Okavango swamp and who was responsible for the phrase “Her tears glistened in the spring sunshine.” He wasn’t enthralled either way.

Without wit, such a book will be charmless and unsympathetic.

In the two published autobiographies I have worked on, some of the funniest and most revealing moments came from the outside.

For surrealism there was the story the producer Don Smith told me about Richards’s forceful mother, Doris, coming to New York when Richards was rehearsing with his band the X-Pensive Winos, a moment when Jack Daniel’s and other stuff was flowing hard and beginning to impair their performance.

It was an incident Richards had forgotten. Doris was watching through the studio glass. The band had been talking for 20 minutes. Smith had shown Doris the talkback button, and she hit it and screamed at Richards, the great Waddy Wachtel, and the great Steve Jordan, “You boys stop messing around there and get to work. This studio is costing money. Nobody understands what you’re saying anyway. I’ve flown all the way from bloody England. I don’t have all night to sit around listening to you yapping about nothing, so get to bloody work.”

“So thanks to Doris’s sudden burst of wrath,” wrote Richards, “we renewed our labours.”

Then there is the story of David Bailey, whose memoir, Look Again, I ghostwrote. When I sensed that Bailey wasn’t being entirely honest, or perhaps was over-romanticizing his relationships with some of the women in his life, I put them together and recorded the dialogue, then printed some of it in the book. First Jean Shrimpton, and then Penelope Tree, his model and girlfriend in the 1960s. At lunch with the three of us, there was a major disagreement about the when and where of the first kiss, as in:

Bailey: That was the first time we did it.

Tree: I swear to God it was not.

And then their breakup:

Tree: I packed two suitcases containing clothes and books and left.

Bailey: I couldn’t find you. You went to Barbados. Then you went off somewhere in the Far East.

Tree: No, first I went to live in a valet’s room on the top story of the Ritz. Which sounds fun, but it wasn’t.

Bailey: I tried to get you back.

Tree: How come I didn’t know about it then?

Keith is right. Memory is fiction.

Or was it me who said it? I can’t remember.

0 notes

Photo

Er erzählte mir von seinem Leben, oder dem Leben, von dem er wollte, dass ich dachte, er hätte es geführt, voller Abenteuer und Gefahr und Glanz. Er ließ seine Vergangenheit romantisch klingen, um uns beide von seiner Gegenwart abzulenken, die ziemlich düster aussah. Er hatte sein Talent vergeudet, sein Geld durchgebracht und stand am Beginn eines langen Abstiegs. Er erzählte eine Geschichte nach der anderen, eine Scheherazade mit dunkler Sonnenbrille ..., und ich sagte nichts. Ich hörte genau zu und glaubte jedes Wort, jede Lüge, auch wenn ich sie als solche enttarnte, aber ich war ebenso überzeugt, dass er es bemerkte und mir nur so viele Geschichten erzählte, weil er meine ungeteilte Aufmerksamkeit und Leichtgläubigkeit zu schätzen wusste. (…) Ich erinnere mich kaum noch an Einzelheiten seiner mündlichen Autobiografie. Ich weiß noch, dass er von bekannten Schönheiten erzählte, mit denen er im Bett war, aber ich weiß nicht mehr, mit wem; ich weiß, dass er von Berühmtheiten erzählte, die er gekannt hatte, aber ich kann mich nicht mehr an ihre Namen entsinnen. Am deutlichsten ist mir noch in Erinnerung, was wir beide nicht aussprachen.

J. R. Moehringer: Tender Bar

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Get ready for the most explosive book of the decade. Page Six has learned that Prince Harry has been secretly writing a memoir for nearly a year, and that he’s sold it to Penguin Random House.

Insiders tell us that Harry — whose schism with the British Royal Family has turned the institution on its head and created a cultural storm on both sides of the Atlantic — has been working on the book with power-ghostwriter J. R. Moehringer.

Pulitzer-winner Moehringer has previously written memoirs for tennis legend Andre Agassi and Nike co-founder, Phil Knight, as well as his own autobiography, “The Tender Bar,” which is currently being made into a movie by George Clooney.

We’re told that a manuscript was due to be turned in in August, but as the lives of Harry and wife Meghan Markle continue to be engulfed in a swirl of drama, the deadline for the sizzling tome has been pushed back until October.

But we’re told the first draft is almost completely written.

A blurb from the publisher, seen by Page Six, says, “In an intimate and heartfelt memoir from one of the most fascinating and influential global figures of our time, Prince Harry will share, for the very first time, the definitive account of the experiences, adventures, losses, and life lessons that have helped shape him.”

It says the book will cover “his lifetime in the public eye from childhood to the present day, including his dedication to service, the military duty that twice took him to the frontlines of Afghanistan, and the joy he has found in being a husband and father” and promises “an honest and captivating personal portrait.”

Transworld, an imprint of Penguin Random House UK, will publish the book in the United Kingdom. It’ll also be released as an audio book.

The release date for this publication is tentatively scheduled for late 2022.

It’s so far unclear what the (no-doubt vast) advance was, but according to the publisher, Harry will be donating the proceeds to charity — despite having recently inked lucrative deals with Netflix and Spotify.

It’s unclear exactly what the book will cover.

But if the project gives the Duke of Sussex an unfettered opportunity to give his side of the story of “Megxit” — the couple’s 2019 decision to step back from royal duties — or settle the score on how the death of his mother, Princess Diana, was handled by the Royals, it will doubtless make history.

Other topics that would leave Brits and Americas alike clamoring for the inside scoop might include his infamous decision to wear a Nazi uniform to a Halloween party in 2005 and the tortured relationship with his father, Prince Charles.

“Insiders are already discussing how much he’ll go in detail about his family after a huge fallout with William and accusing William and Charles of being trapped in their roles on the bombshell Oprah interview,” said a source, “He last saw William a few weeks ago at Diana statue unveiling where, despite sharing a laugh with William, he jumped on a plane that afternoon to go home.”

79 notes

·

View notes